It is a glum time on and off the pitch at Old Trafford, so the latest update on Manchester United’s finances was never likely to lift the mood.

The headline figure from United’s second-quarter results was the £14.5million ($18.2m) incurred in costs for the departures of Erik ten Hag, his backroom staff and sporting director Dan Ashworth.

GO DEEPER

Raphael Varane interview: Real Madrid and Man United differences, Erik ten Hag relationship and retiring

Of that, £4.1m related to Ashworth’s appointment from former club Newcastle United and his shock exit only five months later, contributing to a £26.4m loss over the season already.

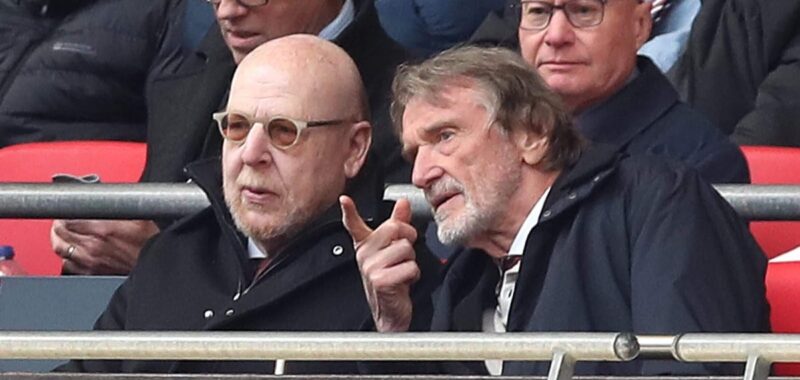

Spending such sums severing ties with a sporting director who had only just got through the door and a manager whose contract had only just been extended exemplifies the waste that was supposed to be a thing of the past under Sir Jim Ratcliffe.

Since completing his minority investment last year, Ratcliffe has embarked upon a range of cost-cutting measures in an attempt to balance the club’s books.

Last week, The Athletic revealed that, having already cut 250 jobs during the summer, United are planning another round of redundancies that will put more than 100 staff at risk. There is unrest among supporters over mid-season ticket price increases, too.

After five consecutive years of losses, Ratcliffe and his INEOS counterparts have warned there are likely to be more unpopular decisions further down the line.

Here, The Athletic breaks down some of the second-quarter numbers beyond the Ten Hag and Ashworth costs, which demonstrate why United feel such measures are necessary.

United debt at £731m despite Ratcliffe investment

The ‘D’ word has never been far away from discussions of United’s finances since the Glazer family’s leveraged buy-out in 2005, which placed £660m worth of debt onto the club. Almost two decades later, that figure stands at £731m.

United’s debt comes in two parts. Around two-thirds — $650m worth — is denominated in U.S. dollars, meaning the pound sterling value fluctuates with changes in the exchange rate. The rest of United’s debt is on their revolving credit facility, which is essentially a credit card the club uses when short of cash.

With Ratcliffe investing £238.5m of his own money into the club over the past year, United have at times chosen to pay down the revolving credit facility debt and did so again this quarter, reducing the outstanding balance by £20m to £210m.

That is only a small dent in the club’s debt pile, though, and further drawdowns up to the £300m limit cannot be ruled out given the club’s struggles to generate cash. Indeed, despite Ratcliffe’s significant investment, United’s £731m of debt has only been reduced by £42m compared to this time last year.

None of this includes United’s transfer debt, which will be specified in more detailed financial results to be released in the coming days. At the end of September 2024, that stood at a net figure of £319m, including a net £154m due to be paid within the next year. Based on most recent figures, only two other Premier League clubs, Tottenham and Arsenal, had net transfer debts above £200m (though Chelsea don’t disclose their figure).

Interest payments increasing – £18.8m this season

Debt is not necessarily a problem if it is manageable, though, and United will almost certainly need to borrow even more money to push ahead with the redevelopment or rebuilding of Old Trafford as planned.

The problems begin to arise when clubs start spending more and more servicing that debt through interest payments, and on that front, United’s costs are gradually increasing.

United paid £18.8m in cash to cover interest charges during the first half of this season, largely in line with the same period last year. But those payments are on the up over the past few seasons, hitting £32m in total for the 2022-23 campaign and then £37m last season.

As the majority of United’s debt originates from the 2005 takeover, these interest charges are the regular, repeated cost that the club pays for the privilege of being owned by the Glazer family.

Cash in the bank down to £95.5m

Those interest payments have contributed to the depletion of United’s cash reserves over the past five years. Whereas the club had £308m in the bank at the end of the 2018-19 season, that rainy-day fund has steadily fallen since.

United’s second-quarter accounts revealed a cash balance of £95.5m. However, that comes after net financing from external sources of £260m (£180m revolving credit drawdown, £80m in equity from Ratcliffe) in the second half of 2024. United are still struggling to generate cash from their day-to-day operations, with negative overall cash flow of £54m during this quarter.

Patrick Dorgu joined United in January (Michael Regan/Getty Images)

A lack of cash to hand is a major reason why United had to show restraint in the January transfer window. Despite Amorim’s squad requiring investment to kickstart a much-needed rebuild, United only spent an initial £26.7m on left-back Patrick Dorgu and 18-year-old defender Ayden Heaven.

What £32.9m loss before tax means for PSR position

Another reason for United’s caution in the market is the need to comply with the Premier League and UEFA’s financial fair play regulations.

Pre-tax profits or losses are the starting point for the Premier League’s profit and sustainability rules (PSR). This season’s three-year cycle will look at each club’s finances during the 2022-23, 2023-24 and 2024-25 campaigns. United have posted pre-tax losses of £196m over those three seasons — with six months of financials for this season still to include.

Although that is well above the maximum £105m limit allowed, United can make significant reductions for spending on women’s football, youth development and other causes considered for the benefit of the wider game.

United avoided breaching last season’s test despite running up a combined three-year pre-tax loss of £313m, so can be hopeful of compliance once more, but recently admitted in a letter to fan group The 1958 that the club is “in danger of failing to comply with PSR/FFP requirements in future years”.

Matchday revenue increases to £52m this quarter

United’s revenues fell by 12 per cent compared to the first half of last season, largely because of missing out on the lucrative broadcasting income from playing in the Champions League.

Matchday revenues rose by £4.4m, however, despite United playing as many home games as they did over the same period last season. Was this the effect of Ratcliffe’s controversial mid-season ticket price hike, which priced all remaining unsold tickets at £66 for the rest of this season?

Not entirely. United’s accounts attribute the £4.4m increase to “strong demand for matchday hospitality packages” rather than general admission, although the price rise is in effect and will be partially reflected in these results.

That increased matchday income looks even more impressive when we consider that United played the same number of home games (15) in the first six months of 2024-25 as a year earlier, but their three European ties were in the Europa League rather than the Champions League. United’s gate receipts per match were up from £5.0m last year to £5.2m this season, even as fans attended less prestigious games.

In a statement, the Manchester United Supporters Trust (MUST) said that ticket price rises will make “only a trivial difference to the financial challenge whilst hugely harming fan sentiment and worsening the mood in the ground, which inevitably feeds through to even worse team performances”.

MUST and other supporters groups are braced for further price hikes when United confirm their ticketing policy for the 2025-26 campaign.

Big jump in football-related amortisation – £102.7m this season

United’s amortisation costs breached nine figures in the opening six months of 2024-25, sitting at £102.7m. In recent years, all but around £1.5m of that has related to player transfer fees and the cost of hiring coaching staff; in other words, United’s football-related amortisation bill topped £100m in the first half of this season and is on target to surpass £200m by season’s end.

Doing so would not quite be unprecedented — but it wouldn’t be far off. The only English club to ever previously top £200m in amortisation costs was Chelsea in 2022-23. It would also represent a huge increase in a short time. As recently as 2021, United’s football-related amortisation bill was £120.3m.

What’s more, clubs with growing amortisation costs can generally point to an improved playing squad. Arsenal’s expenditure here jumped £32m and 23 per cent last season, to £171m, but in return they got a squad that pushed Manchester City right to the wire. United, to put it lightly, didn’t quite hit those heights.

(Top photo: Crystal Pix/MB Media/Getty Images)